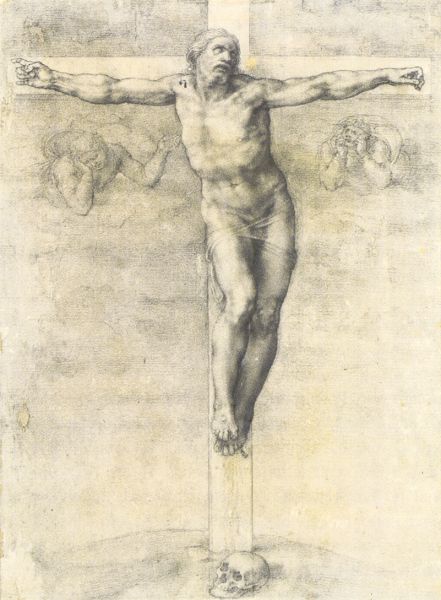

Michelangelo´s Crucified for Vittoria Colonna

Christ is still alive. Virtually offensive is his muscular body, remindful of a Greek God, banishing the humiliating creatureliness of Ecce homo paintings from the beholder’s field of vision. With his daring alteration of the Iconography of the Crucified Michelangelo corresponded to Vittoria Colonna’s personal image of Christ, who, in opposition to the crucial importance her befriended Reformed Theologians assigned to sinister theologia crucis, corrected the repulsive masochist impression of the creaturely suffering Son of God by the bright image of God Apollo. “Be my Apollo”, she addresses Christ in a sonnet.

Previously, Michelangelo had already created Risen Jesus (Santa Maria sopra Minerva, Rome) with a similar ideal body, described by Stendhal as an athlete of remarkable strength. Encouraged by Vittoria Colonna, the artist now even transferred the ideal body onto the Crucified.

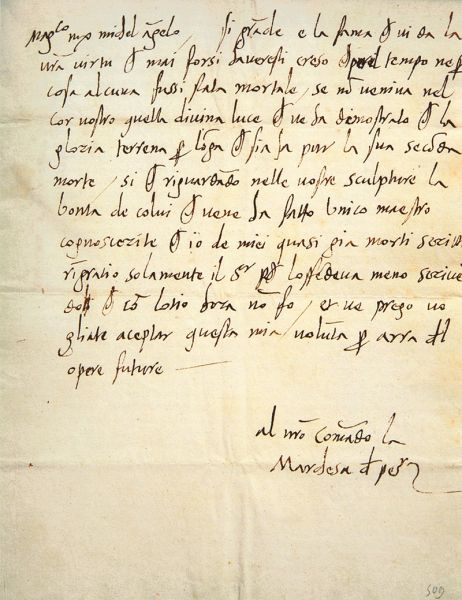

In her letter of thanks to Michelangelo Vittoria Colonna enthuses about Michelangelo’s novel Crucified: „Your Jesus has crucified all the other images”, her drastic, scary pun vehemently condemned the representation of Jesus as “Man of Sorrows” in the art of the Late Middle Ages. “Never have I seen a livelier image of Christ on the cross,” she continues her letter to Michelangelo. “I’ ve been looking at it in the light, in the mirror, and I have never seen anything more accomplished.”

Jesus Christ, the Godman is still alive in Michelangelo’s drawing. Michelangelo gave the Crucified the dignity of the self-aware individual of the Renaissance. He makes the Godson on the cross scrutinize the sense of his crucifixion. Separated from his Godfather, deserted by him, self-reliant in the moment of dying, lonely, nailed on the cross, Michelangelo’s Crucified remains a Self-Assured Individual opposing his Remote Godfather. For certain, Vittoria Colonna encouraged Michelangelo to maintain the human dignity of the Crucified by making the Godson refuse the acceptance of his humiliating death on the cross.

[1] The letter is quoted from KHM 399. Autograph, British Library, London, Ms 23139.

VITTORIA COLONNA

SPIRITUAL MENTOR of MICHELANGELO

Your creations enforce improve the judgement of the beholder.

Vittoria Colonna

Vittoria Colonna to Michelangelo

“So great is the fame granted to you by your virtú that you may never have believed that it will pass away due to time or another cause, had not that divine light invaded your heart, showing to you that mundane glory, though it may last long, will find a second death.

If you recognize in your sculptures the kindness of Him, who has made you the unique maestro, then you will understand that I owe my dead writings to the Lord alone, because I offended him less, when I composed them, than now, where, in idleness, I make nothing. I ask you to accept this will as handmoney for future works.”

At your command

La Marchesa de Pescara

Vittoria Colonna and Michelangelo:

in the years 1541- 1545

„And many times, from Viterbo, she visited him in Rome.“

Vasari

Vittoria Colonna

CANZONIERE FOR MICHELANGELO

and

Influence on the Iconography of Michelangelo

The Living Crucified

Drawing for Vittoria Colonna

Madonna in the Last Judgement

Madonna del Silenzio

Spirituality of Viterbo

in Cappella Paolina

Not casually did active Michelangelo come to Vittoria Colonna’s mind in Viterbo. After the completion of the monumental ceiling frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo painted his opus magnum, the Last Judgement in the years 1538-1541, followed immediately (1542) by the frescoes in Pauline Chapel, ordered by Pope Paul III, who determined that, in Cappella Paolina, the conclave was to take place in future elections of the popes.

With a probablility bordering on certainty, Vittoria Colonna took influence on the iconography of Michelangelo in Cappella Paolina, suggesting to him the novel narrative character of the fescoes, instilling the spirit of Viterbo into the artist.

Vasari documented that she, from Viterbo, visited him in Rome many times. Inner criteria allow the assumption of her impact on Michelangelo.

According to Sidney Freedburg, the frescoes in the Pauline Chapel, Michelangelo’s last paintings, „show a style away from aesthetic effect to an exclusive concern with illustrating the narrative (suggested by Vittoria Colonna?) with no regard to beauty.”

Giorgio Vasari He sent her his sonnets numerously and, for his part, received rymes and prose of the illustrious Marchesa of Pescara, with whose virtues he was in love, and she equally with his. And many times, she visited him from Viterbo and Michelangelo drew for her a Pietà with two dearest puttos and a living Christ on the cross, who, with his head upraised, recommends his spirit to the father, a divine drawing, and a Christ with the woman of Samaria at the fountain.

VITTORIA COLONNA and MICHELANGELO

The inner dynamic of their relationship

Romain Rolland: He loved her more intensely than she loved him.

The inner dynamic of the relationship between Michelangelo and Vittoria Colonna, also the mutual frustrations in the years 1541-1545, are documented and retraceable in their letters, in the sonnets, and in the gift-drawings of Michelangelo for Vittoria Colonna. In the summer of 1542 or 1543, when Vittoria Colonna stayed in Viterbo, Michelangelo created the drawing of the Crucified, whose iconography was influenced by her. While he was looking forward to presenting her the drawing himself, she used Tommaso de Cavalieri as intermediary, because she was keen on showing the drawing around.

Vittoria to Michelangelo: „My dearest Signor Michelangelo, I ask you to leave the Crucified to me for a little while, even though you have not finished it yet, because I want to show the drawing to the noblemen of the most Reverend Cardinal of Mantua”. Michelangelo answers her indignantly, suggesting that, apart from her Crucified, he is also occupied with his his opus magnum, the monumental painting of the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel:

„Had you been aware that love needs no lesson, never would such means have been necessary and though it seemed that I was neglectful, I accomplished what I did not talk about in order to take you by surprise. Now my intention has ben thwarted. Who forgets such faithfulness, does not act fair.”

Your Majesty’s servant

Michelangelo Buonarroti

Unico Maestro et Mio Singolarissimo Amico

“I have received your letter and I have seen the drawing, which has crucified in my mind all the other images I have ever looked at. One cannot imagine a livelier, a more accomplished drawing. Certainly, one could not explain the subtlety of its elaboration. I have been looking at it in the light and in a glass and in the mirror and I have never seen something more accomplished.”

At your command

La Marchesa de Pescara

Michelangelo visits Vittoria Colonna,

too often?

Captivated by errors, tortured by fears, Michelangelo hurries to his beloved Vittoria Colonna: „The more I flee, hating myself hourly, the more I take my refuge to you and less is my soul frightened, when I am near you”.

Vittoria is for Michelangelo the spirited woman, who, enthused and enthusing, purified by water and fire of her corporeality, soars into a lucid day of a purely spiritual existence. So ethereal is she that Michelangelo wonders rather naively: “How can it be Signora that, albeit of divine beauty, you eat and sleep and speak like any mortal creature among us “?Vittoria frequently gave Michelangelo presents, which he accepted with great pleasure, because they offered him the highly desired opportunity of hurrying to her, even visiting her without a gift drawing in return, lacking the time and patience for making a good drawing and longing to visit her instantaneously, because, in her house, he felt like in paradise, in her vicinity he outgrew himself.

Michelangelo to Vittoria Colonna

“Before accepting the things Your Magnificence wanted to give me several times, I wished to make something for you with my own hand to be less undignified of such presents. But after seeing that one cannot buy God’s grace and that it is the worst sin to think little of it, I accept the things mentioned above empty-handed. I know for certain that I, possessing them, will feel like in paradise, not for having these things in my house, but for the opportunity of staying with you, feeling deeply indebted to you for outgrowing myself in your presence, Signora, to whom I recommend myself.

The bearer of this letter will be Urbino, who lives with me. Your Magnificence may tell him when you expect me to have a look at the head of Jesus Christ that your Grace promised to show me. “

Your Majesty’s servant

Michelagniolo Buonarroti at Marcello de Corvi

Vittoria Colonna gives Michelangelo

a gentle brush-off in return.

On 20th July 1543, staying at Viterbo, Vittoria Colonna wrote this letter to Michelangelo:

"Not earlier have I responded to your letter, being an answer to mine, because I thought, did you and I continue writing to each other, I, feeling obliged to do so, and you, wanting to be polite, I would neglect my visits to the Chapel of Saint Catherine, since I could not join the nuns at the customary hour and you would give up the visits of the Chapel of Saint Paul instead of dialoguing with your paintings already in the early morning, from dawn to dusk, the painted figures talking to you in quite the same manner as the living persons talk to me, with the consequence that I failed to perform my duty to the brides of Christ and you failed to perform your duty to the representative of Christ on earth.

-Knowing the endurance of our friendship and the security of our affection tied by the Christian knot, I find it superfluous to procure evidence by exchanging letters with you. Instead, I had rather wait for a real opportunity to serve you, asking the Lord, of whom you have spoken with such a glowing, humble heart at my departure from Rome, he may let me find you at my return, his image renewed in your soul and you animated by the same true faith the Samaritan woman shows in your drawing for me.

I recommend myself to you and equally to your Urbino.

From the Convent of Viterbo, on 20th July.

At your command

La Marchesa of Pescara

Inspite of her polite disguising and careful reasoning, Vittoria rebuffed Michelangelo, restricting the correspondence with him, claiming that their correspondence distracted him and her from more essential duties. In brilliant rhetoric, she points out that the perspectives of their lives, instead of interacting, should parallel each other toward more important aims. Instead of seeking the contact with her, he had rather converse with his paintings in Cappella Paolina, an assignment by Pope Paul III, Obviously, Vittoria wanted to refashion her friendship with Michelangelo, precious as it was to her, from greater personal distance. Permanently grounded on Christian faith, it did not require a bombardment of letters. They should rather wait for an extraordinary opportunity of contact. She warded off burdening intimacy and emotional entanglement.

How did Michelangelo’s react to her rebuff?

His poems, cutting his innermost being in words, as if they were stones, make his suffering of rejected love evident. Even worse is his affliction by the mood swings of his beloved Marchesa due to her bi-polar disorder. Benign affection, shown from time to time, arouses intense feelings of happiness in him. They widen his heart, which is narrowed again the more painfully by her rebuffing him. Affection, then again aversion, benevolence followed by denial, this emotional roller coaster paralyses him and his art, „when you, in your heart, bear death and grace at the same time and my weak spirit, burning up, contracts nothing else from it than death.

In the drawings of couples, dating back to those years, characterized as exploratory drawings by Michael Hirst, Michelangelo, by means of body language, reveals emotional tensions in the relations of couples, suggesting insensivity, ambivalence, shrinking back from the other’s approach, initiated embraces remaining unperformed due to palpable rejection, inhibited affection. Words are spoken into the void. For Vittoria, Michelangelo also drew Jesus and the Woman from Samaria at the well. In her letter from Viterbo, Vittoria wrote to him:

“On my return, He (God) may let me find you with his image renewed in your soul by a lively and true faith, as you have drawn it in my Samaritan woman “.

In case she referred to the same drawing, Vittoria failed the deeper message. Michelangelo´s Samaritan woman is at best pricking up her ears, but she does not reveal a deeply felt faith. The artist ist staging her, when, after drawing water from the well, she is about to part. The motions of her hands emphasize her turning away from the Lord. She does not respond to his gestures. Only a last turn of her head, as a cool bidding farewell prevents his lively gestures from coming to nothing

Vittoria Colonna

Michelangelo’s Spiritus Rector

Thomas Mann: „Michelangelo had come to earth twice, first as a model of himself, in bad clay, but then thanks to her influence, in a rebirth, as a perfect work of art in stone by her chastising and bridling his wild nature, adding what was missing, rasping off what had been rough and excessive in him.“ It was up to her to shape him in a similar manner as he forms a work of art, because in him were neither power nor will: „Make a drawing of myself, as I make a drawing on a white sheet of paper that contains nothing, but later reveals what I intend. “ Evidence for Vittoria’a inspiring influence on Michelangelo’s iconography can be traced in his poems, assigning to her the role of his muse and of his spiritus rector.

Michelangelo was tormented by metaphysical fears, especially in the forties of the Cinquecento, when he created the Last Judgement, a work that was wearing him out. In the midst of the damned, the beholder discovers an empty human skin with Michelangelo’s features. Michelangelo, in a poem, he wrote on the backside of a letter to Vittoria Colonna, is handing to her an empty sheet of paper to note down her helpful advice for his desperate quest for salvation. “I am handing the white sheet of paper to your holy ink for love to free me and for pity to write down the truth, so that my soul, free in itself, does not surrender to error in the short rest of life and I live less blindly”.

In a letter from Viterbo, Vittoria Colonna expected Michelangelo’s progress in his spiritual life on schedule until her return to Rome.Vittoria wanted to find him „lively in true faith “, meaning by liveliness in true faith, a blessed feeling in the sense of Valdès, giving her wings to an upswing to divinity: „Oh, may I feel the effect of his force, which makes me untie the knot, which binds me to my human shroud. “

Michelangelo frustrates Vittoria Colonna.

Her Canzoniere cut no ice with the artist.

The greatest proof of her deep attachment to Michelangelo is the vellum codex Vaticanus 11539 containing one hundred and three of her sonnets. Vittoria selected them personally and had them written in calligraphy for her singolarissimo amico, choosing Rime Spirituali, presumably with the intention of spiritualizing his art, encouraged by Michelangelo himself, who expressed his need of being formed by her.

However, the inspiring effect of her Canzoniere on Michelangelo did not appear. The beatifying impact of her lyrics on him, so much desired by her, cannot be traced. He had the one hundred and three sonnets she gave him for a present and the other forty sonnets she sent him from Viterbo bound together in vellum. Michelangelo guarded her present like a treasure, refusing to lend this unique gift to other people, inventing lame excuses, the more so, because he was one of the three persons, honoured by this extraordinary present of a Canzoniere by Vittoria Colonna. But in contrast to the philologist and literary pundit Pietro Bembo, who interpreted single sonnets by the poetess intrinsically, Michelangelo expressed his thanks by means of a conventional sonnet, as was the custom in Humanist circles: He would have liked to give the poetess an adequate poem for a counter gift but, of course, he was unable to compete with her Greatness. In contrast to his expressionist love poems (no sonnets!) to Vittoria Colonna, cutting his overwhelming feelings in words, as if they were stones, overpowering feelings, which blow up any frame, this sonnet is stilted and sophisticated. Embarrassing are the „thousand attempts of a counter-sonnet he did not make. Moreover, the confession of his failure spared him the effort of delving into Vittoria’s poesy.

Michelangelo was fascinated by Vittoria’s personality and not primarily by her poetry. Her personal vicinity was an existential necessity for him. His artistic imagination was enkindled by her beauty. Therefore, he had to catch sight of her, but he could not meet her often enough. Here, she frustrated him. He suffered unutterably, when she withdrew from him. Not seeing her, bordered on forgetting, because Michelangelo was in need of immersing himself in her face: “Oh, make one single eye of my body so that no part be on me that cannot enjoy the sight of you”.

Condivi, his biographer emphasizes that Michelangelo sent Vittoria Colonna love poems in great numbers. But Vittoria did not answer them. It is her dead husband Ferrante d’Avalos, to whom she addresses her Rime Amorose. How much we may wish so, the sonnets of Michelangelo and Vittoria Colonna are not synchronized. Correspondences are casual- They were not passing the ball to each other. Michelangelo was passionately in love with Vittoria Colonna, emphasizes his biographer Condivi. He gave stirring utterance to his passionate but ultimately frustrated love to Vittoria in his sonnets.

In spite of proper distance she imposed on him and in spite of the slightly condescending tone the aristocratic lady struck, when conversing with an artist, Vittoria was equally mesmerized not only by his art but also by Michelangelo’s personality: unico maestro et mio singularissimo amico – she addresses him in her thanksgiving letter for the present of the drawing of the Crucified., giving a conventional phrase a most affectionate touch by surpassing the first superlative, though apparently not surmountable, by the second: “my most singular friend.”

Vittoria was Michelangelo’s Sibyl, freeing him from his sensuality, carrying him away through water and fire to a serene and lucid day, transfiguring him: “A model of minor value I became something of a more perfect kind by you.” Owing to her male intelligence and her slightly male features, reminding the beholder of a virago in spite of her graceful femininity, Vittoria Colonna embodied Michelangelo’s ideal of man, comprising male and female qualities. His beloved Marchesa was for him a man in a woman, therefore a God, un uomo in una donna, anzi uno Dio! Therefore, he wrote to Fettucci, when she died. Death deprived me of a great friend. Morte mi tolse un grande amico.

VITTORIA COLONNA and MICHELANGELO

HERETICAL PAIR

Vittoria Colonna’s

Canzoniere for Michelangelo reflects

Religious Authenticity of her Rime Spirituali

Presumably, in the years 1541-1543, when, from Viterbo, she frequently (Vasari) visited him in the Vatican in Rome, where he decorated Cappella Paolina with frescoes, Vittoria Colonna gave Michelangelo her sonnets for a present she had primarily poetised in the forties. Michelangelo had them bound in vellum, the booklet being still extant as Codex Vaticanus Latinus 11539. The greater number of sonnets are dedicated to Reformed Theology and owe their genesis to the discourses Vittoria Colonnas had with Gasparo Contarini (Sola Fide), and with Bernardino Ochino (Theologia Crucis). The Humanist, well versed with rational thinking, also minimizes faith as an expedient for lacking recognition of God here on earth. She poetises her swaying between faith and scepticism and she dares reproach God for lacking response to her lively faith. The Renaissance Aristocrat and Humanist, glorifying Apollo as thepainless Greek God of light, in a sonnet, addresses Jesus: „Be my Apollo”. Painfully she struggles with internalizing the Godson on the cross, the core message of Theologia Crucis, solving her dilemma by emphasizing, in her sonnets, the godly almightiness of Jesus even on the cross.

The strict Renaissance feudal lady, severely disciplining the serfs on her estates, vehemently declined the doctrine of Juan de Vadés, Christ died on the cross for the evil and the good people alike. Vittoria Colonna pictures and makes audible the evil world in her sonnets, again and again thematizing the malice of people in the Canzoniere for Michelangelo to illustrate the necessity of a punishing God.

The activity of the Holy Spirit as inner enlightenment in the well-born souls of the Spirituali in Viterbo, withdrawn from the will of man and in need of imputed divine grace, enthralled the poetess, who equated inner enlightenment with poetical inspiration, understanding herself as medium of the Holy Spirit: “Ma dal foco divin, ch`l mio intelletto sua mercè infiama, convien che’escan queste faville.”

But then Vittoria Colonna made similar experiences as Mother Teresa, who, at the end of her life, sincerely confessed that in the past fifty years of her life she had never felt the presence of God in her soul. After the poetess, staging herself with a plough in her hands, digging deep furrows into the dried earth of her soul, but only to wait for reshreshing rain from Heaven in vain, so that she must fear that the vines do again grow stunted grapes, she, in the tercets, directs the breath- taking request to HIM, he, at long last, shall himself reveal so that she can ward off “dark thoughts”. In another sonnet, she, humourously proposes to God to send her an eternal lamp into her soul, to inflame her, who is now depressed by the mere tepid divine glow.

With enviable self-confidence, Vittoria Colonna integrates sonnets, which, in departure from the spirituality and reformed theology of Ecclesia Viterbiensis, document religious subjectivism. In one sonnet the poet deplores the failure of contemplative spirituality practiced in Viterbo, in psychic predicaments. „I believe that one cannot cherish lively hope of etermal promises, if angst, this cold fog, constricting our heart, resists the flaring flame”. In the Armageddon, Vittoria, after lifelong practiced invocation, she confides herself to the magical force of the name of „GESU”: un grido alto et possente.

As she feels left alone and forsaken by god without divine response to her lively faith according to sola fide, the poetess returns to religio, the reconnection of the human being to a tangible God by transferring Jesus, the Son of Man, to the shores of Ischia and she by ties her bark up to him with a bond of love, knotted by faith: “I fasten my bark at the living rock Jesus, whom I trust so that I can withdraw into this haven at any hour, whenever I wish.”

Humble expectation of the Holy Spirit is one leitmotif of Rime Spirituali according to the doctrine of Viterbo. Ardent longing of divine fulfilment already here on earth is the other underlying melody in the polyphone complexity of her sonnets spirituali corresponding to her female Renaissance personality. She is not satisfied by small portions of divine mercy she experiences now and then. She desires to recognize and to experience God in his whole complexity, already here on Earth.

VITTORIA COLONNA

CANZONIERE MICHELANGELO

TWO DIVERSE APPROACHES

Religious subjectivism, appertaining to Vittoria Colonna as a Female Renaissance Personality and conditioning her female authenticity in her Rime Spirituali, can only be brought to the fore by empirical research of single sonnets. The analysis of Vittoria Colonna’s subjectivism and female authenticity also necessitate the comparative interpretations of several sonnets of the same macro-theme in order to unfold the spiritual and mental complexity of the Renaissance Poetess, which has never been thematised so far.

Instead, the complex Renaissance-Personality of Vittoria Colonna has been streamlined to a faithful adherent of Reformed Theology by means of eclectic interpretation of her Rime Spirituali. It is true, Abigail Brundin refers to Constance Furey: Intellects inflamed in Christ: Women and Spiritualized Scholarship in Renaissance Christiani, emphasizing: „Furey identifies a new kind of spiritual community that was rooted in mutual intellectual endeavour and the desire for personal and communal illumination “. However, what regards Vittoria Colonna’s Canzoniere for Michelangelo, Brundin restricts her own interpretation to “the evangelical genesis of the poet’s thought “and reduces the interpretation of the sonnets, composed by a Renaissance Poetess, to the eclecticistic selection of „references to reformed spirituality “

VITTORIA COLONNA

INFLUENCE ON MICHELANGELO’S ICONOGRAPHY?

VITTORIA’S LIVING CHRIST ON THE CROSS

MADONNA alias VITTORIA IN “THE LAST JUDGEMENT”

SPIRITUALITY of VITERBO

in

CAPPELLA PAOLINA

The Canzoniere for Michelangelo, the sonnets of which were selected and put together by Vittoria Colonna personally and single-handed, provides the ground-laying text for her formative influence on Michelangelo’s drawings and frescoes in the years 1541-1545, which becomes evident in her thank-you letter to Michelangelo for the drawing of the Crucified.

Michelangelo’s Living Christ on the Cross

Gift-Drawing for Vittoria Colonna

In her sonnets thematising Theologia Crucis, Vittoria Colonna repeatedly suggests her aversion against the humiliation of the Godson by his disgraceful death on the cross and the creaturely suffering of the masochistic Man of Sorrows in the paintings of the late middle ages. To maintain the divinity of the Crucified, Michelangelo, according to her wish, drew Christ living on the cross without the crown of thorns, without physically evident wounds, and with the ideal body of a Greek God. Jesus Christ, the Godman, is still alive in Michelangelo’s drawing. Michelangelo gave the Crucified the dignity of the self-aware individual of the Renaissance. He makes the Godson on the cross scrutinize the sense of the unfathomable happening of his crucifixion. Separated from his Godfather, deserted by him, self-reliant in the moment of dying, lonely, nailed on the cross, Michelangelo’s Crucified remains a Self-Assured Individual opposing his Remote Godfather. For certain, Vittoria Colonna encouraged Michelangelo to maintain the human dignity of the Crucified by making the Godson refuse the acceptance of his humiliating death on the cross. Sylvia Ferino-Pagden “It should be emphasized that Michelangelo’s drawing of the Crucified with his antique-like muscular body is an offence against the conventional representation of the crucifixion without any visible wounds, except for the nails in hands and feet, moreover without the crown of thorns.” In her letter of thanks to MichelangeloVittoria Colonna enthuses about Michelangelo’s novel Crucified: „Your Jesus has crucified all the other images”, her drastic, scary pun, vehemently condemning the representation of Jesus as “Man of Sorrows” in the art of the Late Middle Ages. “Never have I seen a livelier image of Christ on the cross,” she continues her letter to Michelangelo. “I’ve been looking at it in the light, in the mirror, and I have never seen anything more accomplished.

Christ is still alive. Virtually offensive is his muscular body, remindful of a Greek God, banishing the humiliating creatureliness of Ecce homo paintings from the beholder’s field of vision.With his daring alteration of the Iconography of the Crucified, Michelangelo corresponded to Vittoria Colonna’s personal image of Christ, who, in opposition to the crucial importance her befriended Reformed Theologians assigned to sinister Theologia Crucis, corrected the repulsive masochist impression of the creaturely suffering Son of God by the bright image of God Apollo. “Be my Apollo”, she addresses Christ in a sonnet.

Madonna alias Vittoria Colonna

in the Fresco “Last Judgement”

by Michelangelo

Vittoria Colonna’s

Influence on Michelangelo’s Capolavoro

Fifteen sonnets to Maria in her Canzoniere for him were meant to make Michelangelo aquainted with her Humanist remake of the Holy Virgin. None of these sonnets is a conventional invocation of Maria as the advocate and mediatrix of man with God. Vittoria Colonna’s sonnets thematise her ontological interest in the interaction of divinity and humanity in this singular woman, to whom the poetess even grants decisive influence on the earthly existence of the Godson in a sonnet

Vittoria Colonna:

„Only little inferior to the divine son is the eternal mother

The Renaissance Poetess demands an adequate place of the godmother beside her divine son, enthusing that Maria is the most perfect woman: “inflamed by glowing love, eternalized in her beauty, fully blossoming in the wealth of her emotional life.” With imaginative empathy, Vittoria Colonna describes the plentitude of being in this woman, who unites human and divine entities in her person.

While the Church sees in Maria the maidservant of the Lord and the godmother embodies for Bernardino Ochino a simple woman out of the people, Vittoria Colonna endows Maria with the intelligence of a Humanist like herself and, as a matter of consquence, Vittoria Colonna determines his mother as the trustee of her Godson’s inheritance on earth after his death. And for the creative theologian, the assumption of the godmother into the glory of Heaven in corporeal beauty is the proof for the acknowledgement of the divine/ female human identity of the Godmother by the threefold male God.

The Humanist Godmother of Vittoria Colonna

in Michelangelo‘s The Last Judgement

In contrast to the medieval paintings of the Last Judgement, in which the Holy Virgin as a rigid icon is kneeling on the side of the world judge with her folded hands raised to her son in a worshipping attitude, Michelangelo unites son and mother in a suggested mandorla, thus, in a sophisticated refined manner, typical of Vittoria Colonna, which has been overlooked by posterity, suggesting a quasi-equality of the transfigured mother with her son. In her transfigured state Michelangelo’s Madonna is more soaring from than sitting on the throne offering two seats, on which she had taken place beside her son, before he stood up to pass his verdict on mankind. It is in this last moment before sentencing that Michelangelo presents the divine judge. With inner coherence Michelangelo awards the features of his beloved Marchesa to this novel, almost revolutionary Madonna, who was her creation. He stylyses the transfigured beauty of the godmother in transcendental bodiless grace, simultaneously suggesting in the gestures of this new humanist Godmother personal distance from her wrathful son judging men in anger. Instead of worshipping Jesus with folded hands according to medieval iconography, Maria holds her hands crossed over her breast in a gesture of self-protection from the wrath of the world judge, who is her son, pitifully turning to the men, on whom he is sitting in judgement.

VITTORIA COLONNA

Cappella Paolina

Heretical Spirit from Viterbo into the Vatican!

How intensely she cared for Michelangelo is proved by her letter to Priuli, Reginald Pole’s companion.Caringly, Vittoria Colonna tried to make the working conditions easier for seventy-year Michelangelo, who exhausted himself with the painting of the frescoes in Cappella Paolina imposed on him by Pope Paolo III: “What regards Michelangelo, it is only a tiny matter I request from you, namely the black glass from Venice, which I want to furnish with a gilded pedestal to improve his sight in painting, because he is exhausting himself in Cappella Paolina.”

The infiltration of St Paul’s Conversion with the spirit of Viterbo in the fresco reveals Vittoria Colonna’s influence. She took care for the visualization, executed by Michelangelo, of the heretical mysticism of Viterbo in the very centre of the papal church. According to Vasari, it was from Viterbo that she often visited Michelangelo in Rome, presumably in Cappella Paolina, as before Michelangelo had only allowed Vittoria Colonna, who suggested to him her novel iconography of Humanist godmother, to visit him in the Sistine Chapel, while he was creating his opus magnum, the Last Judgement.

Michelangelo designed the confession of Saint Paul as an inner experience. Jesus Christ is not sitting enthroned high above in the glory of his power, like in conventional paintings, but he is bending deep down to Paul, his future apostle, as if God wants to approach him on a human level, while Paul is lying stretched out on the earth, hit by the beam of divine light. Meanwhile, the beam has dissolved into a diffuse light, which is being watched by the bystanders with wide-open eyes, while Paulus is still lying on the ground, keeping his eyes closed. Although assisted by somebody, he remains in his absentmindedness, as if his conversion, as a kind of inner enlightenement, is still going on or as if Paul is meditating his awe-inspiring contact with God or as if he has not yet arrived at a personal decision in favour of the God of the Christians. Michelangelo’s Conversion of Saint Paul is in no case the automatic consequence of an indoctrination from above in a spectacle of divine revelation, but it is an inner process, in the course of which Michelangelo’s Paulus, as a self-reliant, human individual of the Renaissance, takes a personal decision to enter into the service of Jesus Christ.

It struck Antonio Forcellino (Michelangelo A tortured life) that the painter populated the scenery with a host of anonymous believers in simple garments (the “select souls” of Viterbo?) perhaps to set off the Spirituali from the power-conscious Cardinals, who, in their pompous ornates, assembling in Cappella Paolina to elect a new pope, distance themselves from a genuinely Christian community in their ambitious rivalry.

As Michelangelo’s mentor in Rome and Viterbo, Vittoria Colonna did not spiritualize his art by means of her sonnets - they left him unimpressed - but through discourses with the creating artist in Sistine Chapel, to which the artist only granted personal access to her, and during her visits in Cappella Paolina, where she travelled from Viterbo.