ESSAY

VITTORIA COLONNA

EXPERIMENTING WITH THE DIVINE

Michelangelo´s Crucified for Vittoria Colonna

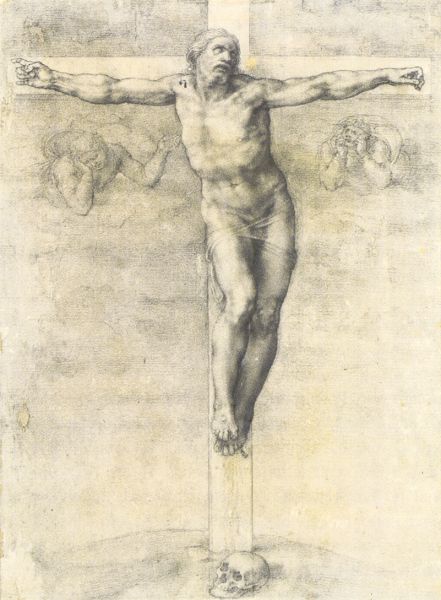

Christ is still alive. Virtually offensive is his muscular body, remindful of a Greek God, banishing the humiliating creatureliness of Ecce homo paintings from the beholder’s field of vision. With his daring alteration of the Iconography of the Crucified Michelangelo corresponded to Vittoria Colonna’s personal image of Christ, who, in opposition to the crucial importance her befriended Reformed Theologians assigned to sinister Theologia Crucis, corrected the repulsive masochist impression of the creaturely suffering Son of God by the bright image of God Apollo. “Be my Apollo”, she addresses Christ in a sonnet.

Previously, Michelangelo had already created Risen Jesus (Santa Maria sopra Minerva, Rome) with a similar ideal body, described by Stendhal as an athlete of remarkable strength. Encouraged by Vittoria Colonna, the artist now even transferred the ideal body onto the Crucified. In her letter of thanks to Michelangelo Vittoria Colonna enthuses about Michelangelo’s novel Crucified: „Your Jesus has crucified all the other images”, her drastic, scary pun vehemently condemned the representation of Jesus as “Man of Sorrows” in the art of the Late Middle Ages. “Never have I seen a livelier image of Christ on the cross,” she continues her letter to Michelangelo. “I’ ve been looking at it in the light, in the mirror, and I have never seen anything more accomplished”. Jesus Christ, the Godman, is still alive in Michelangelo’s drawing. Michelangelo gave the Crucified the dignity of the self-aware individual of the Renaissance. He makes the Godson on the cross scrutinize the sense of his crucifixion. Separated from his Godfather, deserted by him, self-reliant in the moment of dying, lonely, nailed on the cross, Michelangelo’s Crucified remains a Self-Assured Individual opposing his Remote Godfather, who imposed this shameful death on him. For certain, Vittoria Colonna encouraged Michelangelo to maintain the human dignity of the Crucified by making the Godson refuse the acceptance of his humiliating death on the cross.

With a mental vitality, extraordinary among all women of all ages, Vittoria Colonna insists on religious self-determination, taking her own ways as a God Seeker. Her inner discontent estranged her from male doctrines of salvation so that she also searched her own female way as a God-Seeker The progress of her fanatical search for God obstructed by dichotomy between intellect and faith brings her close to us. It is true, the poetess, according to Reform Theology, praises Inner Faith as the only way of getting justified to God. But there are sonnets, in which she sees faith as an empty promise and an expedient for the fact that the recognition of God is not accessible to man in his earthly existence. As her intellect cannot grasp God, Vittoria Colonna again and again turns to scepticism. With giant strides she would follow. Christ along Via Dolorosa as a cross-bearer, could she catch sight of Jesus Christ with her own eyes, as Saint Peter did.

Or could she at least feel e a divine light in her soul. With mystic contemplation of God being reduced to some scare sparks now and then, the female personality of Renaissance-Humanism cannot be secure whether her little hope for Heaven does not resemble fragile glass Of course, the mysticism of Juan de Valdés, who interpreted Inner Faith as a gracious gift of the Holy Ghost to Chosen Souls met Vittoria’s great longing for conflation with the Divine already in her earthly life. She hoped to experience the “Divine Flame of the Holy Ghost” as an invisible strength proclaimed by the poetess as source for inspiration of her spiritual verses: “From the Divine Fire inflaming my Intellect, these sparks spring up.” If at all, the poetess only seems to have felt the inspiration by the Holy Ghost as a momentary presentiment. Instead of being fulfilled by the Divine, Vittoria Colonna shares the feeling of excruciating inner emptiness with Mother Teresa, who admitted to her Confessor at the end of her life that, for half a century, she had not felt the presence of God in her life. Other than the male mystic Juan de Valdès, for whom the impact of the Holy Ghost on the Soul was absolute truth, whereas he ignored his painful absence. Vittoria Colonna gave utterance to the drought inn her soul in her Rime Spirituali. She compared herself with a withered branch at the tree of life in deepest shadow. With her courageous truthfulness, she already made great impression on her contemporaries and is more convincing today than the mystic Juan de Valdès

She got carried away for a utopian life design, when she established herself in the community of the Spirituali in Viterbo to live in vicinity to Reginald Pole, whom she idolized, in passive expectation of the inspiration by the Holy Ghost with the consequence that the contemplative life style paralysed her lively temper. In Viterbo, Vittoria Colonna fell seriously ill physically and above all psychically, because the contemplative life-style intensified her inner restlessness, which exploded in psychoses.

The proud Renaissance Aristocrat found it hard to overcome her inner aversion to Martin Luther’s sombre Theologia Crucis, which was adopted by the Spirituali of Viterbo as the crucial doctrine of salvation, because according to her Aristocratic upbringing, Christ’s divine dignity was trampled down by his shameful death on the cross. As she could not bear creaturely suffering of the Man of Sorrows, the Humanist united Christ with the painlessly radiating Greek God Apollo in her personal image of God and had Michelangelo draw the Crucified with the body of a Greek God.

As enforced passivity ignored the human innate drive to make the divine available, Vittoria was worn down by the futile expectation of divine enlightenment. Thanks to her intellectual independence and resourceful eagerness to experiment, she beat new paths to get hold of the divine at least in her poetry: Vittoria Colonna resorted to Soteriological ways she invented for herself, taking refuge to Jesus the Son of Man, whom she took out of his remote Biblical context to transfer him to Ischia’s shores so that she could hurry to the beach to fasten her life- boat to her personal Jesus. Single-handedly, she performed her religio, her personal reconnection to God. However reticent Jesus could not completely extinguish her scepticism. So, the boat remained on the shore, ready to set sail again. In case, the chords should break, it was possible to embark again on a new Odyssey of Personal God-Seeking.

Like a naïve woman from the common people, the intellectualized Aristocratic Lady clings to magical thinking. All her life, she practised the scream “Gesu” in extremis, - “un grido alto e possente” - to have it at her finger tips in Armaged don. Her magical relation to Nature, by whose beneficial aura she felt embraced with security and strength, was a kind of substitute divinity withheld from her grasp. The juniper tree that does not surrender to storms, but closes its crown and resists, her beloved rock of Ischia standing firm against il turbato mar, are transfigured by the poetess into role models for female sovereignty and proud female self-assertion against hostile Fortuna.

Vittoria Colonna did not identify herself with any doctrine of salvation. She remained on the way as a fanatical God-Seeker. While she, in the gown of Michelangelo’s Sibyl transformed by herself from a prophet into a God Seeker, with flaring torches in both hands, is flashing lights into the eternal night after God in vain, she suddenly, obeying an impulse, performs a U-Turn to her own surprise. Could it not be, it occurs to her, that she missed an encounter with God here on earth, because she was seeking him in the Beyond? “There she is, the blind woman”, Jesus could reveal himself to her in blaming tone. “In spite of bright rays, she did not recognize her beautiful sun.”

The Renaissance Humanist also wants to see God at home on earth.